Yury Toroptsov remembers the moment he fell in love with Céline Dion.

In 1997, he was on a layover in South Korea. Flipping through the channels on his hotel room TV, halfway through getting dressed to go out, he caught a glimpse 1996 music video for “It’s All Coming Back to Me Now”—six minutes long, starring Dion in a floor-length, long-sleeve, white lace nightgown, following her through a night of terror in which she is haunted by the ghost of her lover, who has died by crashing a motorcycle into a tree.

Toroptsov was taken in by the spectacle, and the voice—the sheer magnitude of Céline, the Quebecoise bi-lingual international superstar, whose 1997 power ballad about Leonardo DiCaprio dying is one of the most beloved and most reviled in modern history. Toroptsov didn’t see the whole video at first, so he sat on the bed and waited for the Asian MTV-equivalent to repeat it. Sure enough, they played it over and over in the course of the next few hours. “I was hooked,” he told me. “By the time I was ready to leave the hotel room, I knew where I was going! To the largest music store in Seoul to buy Céline’s CD. It was un coup de foudre, as they say in French. A strike of thunder which announces sudden affection.”

Toroptsov’s fandom strengthened over the next several years, spent in New York City and Paris. In 1998, sat on the steps outside Madison Square Garden, knowing that Dion was inside. In 1999, he had a friend use her American credit card to sign him up for Céline’s official fan club. In 2002, he says, he used a journalist friend’s name to sneak into a French press junket, at which he blanked. Given an opportunity to ask a question, in a language he didn’t yet speak, Toroptsov told her only, “You look gorgeous.” (He says that Dion responded by tossing some flower petals off of the table she was sitting at.)

He didn’t have time to explain to Dion how important she was to him—how her artistry and her journey from rural poverty to international success mapped out a life he was chasing for himself. So he definitely didn’t have time to explain that he had recently launched a fan page about her online. Or that the fan page was an online repository of other people’s dreams about her.

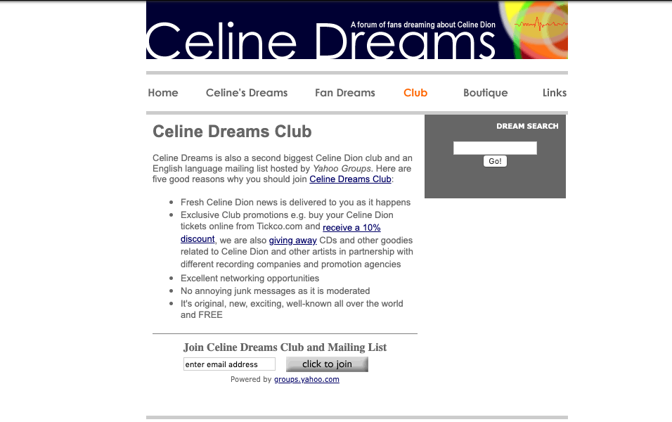

The premise of Celine Dreams was simple: Anyone who had a dream about Céline Dion could submit it through a contact form and then wait, to see if Toroptsov would pluck it out and interpret it for them. The dreams came from the U.S. and the U.K. and Estonia, from teenagers and 40-somethings, men and women. In many, Dion appears as a friend or a mother. In others, she is dead. In one of Toroptsov’s favorites, a 20-year-old girl named Bella says she dreamed that she asked Dion for an autograph, while really tricking her into signing adoption papers.

Celine Dreams was a bit of a sensation. Toroptsov never lacked for dream submissions, and at the turn-of-the-century—before the internet was a corporatized monoculture repeated across only a handful of giant web properties—a scrappy, DIY fansite could easily build an audience by climbing up search rankings and encouraging active participation. For years, Celine Dreams appeared in the first page of Google and Yahoo search results for Céline Dion—a distinction now reserved for Céline Dion’s official website, Céline Dion’s Wikipedia page, Céline Dion’s Twitter page, Céline Dion on Spotify, Céline Dion on YouTube.

And then it shut down, blinkering out at the same time as thousands of other fansites. The whole ecosystem slid into the digital ocean slowly, but pretty much all at once, like a famous ship.

Toroptsov was born in the far-eastern wilderness of the Soviet Union in 1974, raised by his mother, a schoolteacher, and his step-father, who was employed by the government to hunt wild boar. His only official education in dream analysis comes from an intro-level psychology class he took as an elective at the New School in the late ’90s, when he came to New York to get a master’s degree in management. He was enchanted by Freud and Jung and the idea that there was a science to dreams. And he was also enchanted by Céline Dion, so.

“Celebrities occupy this collective consciousness, the way gods would occupy the minds of people centuries back,” Toroptsov says. “That sacred space is important. People project things on to these people who are publicly visible.”

Toroptsov taught himself web design in order to launch Céline Dreams while working for the United Nations in Paris. The site’s original version was a text-heavy page broken into navy blue and grey rectangles. As Toroptsov’s skills improved, he added some magenta, some scrolling banners, and ever-rotating photos of Céline. Even a logo, eventually: a bouquet of multi-colored circles with a red encephalogram cutting through them.

It took some effort to decide which dreams were real and which were fake, but he usually chose which submissions to respond to based on what he found personally striking. For instance: “Céline was sitting in a place I do not know at all, but I had a feeling that I had known that place,” a Canadian woman named Pauline wrote in. “It was obvious to take a picture of her. And here is the whole strangeness of my dream. That woman didn't look like Céline, but I felt it was her. When I was about to take a photo of her, I realized I had no plates in my camera.”

Toroptosv’s interpretation was characteristically crisp and polite. “What seemed to be the right place and the right time is actually an illusion,” he responded. “The lack of clarity in the dream might suggest a situation you find yourself in at the moment. The best strategy to advance when the road is not completely clear is to slow down and take one step at a time.” Toroptosv signed off as he usually did, with “Thanks for sharing your dream!”

Céline Dreams became so popular that Dion’s team listed it on her official website (though Dion’s publicist declined to comment on whether the singer is personally aware of the site). Concert-ticket resellers paid Toroptsov an average of 100 Euros a month each to link to them. He made commission on Amazon referral links in his site’s “boutique.” He became part of an ecosystem of high-profile Céline Dion fans—the type of mythological fandom figure that’s sometimes referred to as a “Big Name Fan,” or BNF. Toroptosv was aware that a lot of people find Céline Dion tacky, or over-the-top, but he didn’t care. Many of those people, he says, would still listen to “My Heart Will Go On” all the way through to the end if they were sitting somewhere alone.

“I knew some people took me for an idiot,” he says. “Well, so what? For me, I believe that for something to exist on this scale within a popular culture, it cannot be a thing that doesn’t mean anything or doesn’t have any connection to the people of that time… It touches something and there is some truth in this.”

Though the basic conceit of Céline Dreams sounds hallucinatory now, it was actually pretty common for fansites to have dream sections at the time. Fans going online to talk about the subjects of their devotion were often also looking for some outside expertise on why their favorite stars loomed so large in their minds. It made sense to turn to dreams for some hints.

Céline Dreams was at its peak from 2003 to 2007. It was also just one in a sea of thousands—hundreds of thousands, maybe—of fansites during the early aughts, all enabled by platforms like GeoCities, Angelfire, and Tripod. Supplemented by the community features of Yahoo Groups, fan-specific forums, and email listservs, these sites were a major factor in what made the early web seem so promising. For a few years, it looked like people might use the internet primarily to talk and teach about things they loved.

Yahoo Groups, a combination of listserv and forum features which launched in 2001, the same year as Céline Dreams, was one of the first tools that fans used to congregate en masse online. In 2010, Yahoo said it had more than 115 million users in 10 million groups. At the same time, the free web-hosting service GeoCities was home to about a third of the fansites that Céline Dion’s team linked to on her official website. Launched by Yahoo in 1994, it was a hotbed of fan pages, dominated by Harry Potter, The X-Files, Sherlock Holmes, and Hanson. According to an incredibly buggy search engine released last year to help former users travel back in time, there were about 1,200 pages dedicated to Céline Dion.

Toropstov shut his site down when he left the United Nations in 2011 to become a full-time artist. Today, Céline Dreams itself is available only through the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine—a piece of software developed in 1996 to crawl websites and take snapshots of them at various points in their history. After Toroptsov let the domain go, it first became a website advertising high-end escort services in London. Now the homepage is titled “Anniversary Gift Ideas,” but redirects immediately to an order form for a company that sells custom puzzles.

More of these fansites disappear all the time, and even the Wayback Machine isn’t able to keep even a near-perfect record. Toroptsov’s project, and the work of his “competitors,” are vanishing in what information scientists have long been referring to as the “digital dark age.” “However widely the myth of the automatically archival Internet has spread over the past 70 years, the fact is that the system of networked computing utterly fails as a memory machine,” the UC Berkeley media researcher Abigail De Kosnik writes in her 2016 book, Rogue Archives. “The internet and computers do not constitute the greatest archive in human history, but rather the reverse.”

GeoCities shut down in the U.S. in 2009, taking whichever of its thousands of fansites that hadn’t been archived by volunteers with it. And last October, Yahoo’s owner, Verizon, stopped letting anyone add new content to their Yahoo Groups. The company plans to remove almost everything ever posted in them at the end of this month. (Yahoo Groups was neglected by Yahoo for years, and the rise of Facebook and other, more seamlessly functioning social platforms didn’t help with user retention.)

Preservationists at the Internet Archive and the Organization for Transformative Works, which runs the fan-owned fanfiction platform Archive of Our Own, have been coordinating to save what they can. They’re aided by a Tumblr-based group called the Yahoo Groups Fandom Rescue Project, which has been sharing tips on how to use Verizon’s buggy download tools and coordinating in a 200-person Discord channel. Despite these preservation efforts, things will be lost. “The history of internet culture is a history of lost and destroyed information,” The Daily Dot reporter Gavia Baker-Whitelaw wrote about Yahoo Groups’ official destruction this fall.

Every few years the surface of the social web refreshes. Tumblr had its biggest spike in new users just as Céline Dreams was shutting down—its subcultures later moved on to plunder the broader web, remaking Twitter into standom’s Tower of Babylon. Fandom is more visible online now than ever. At the same time, much of its history is gone, or dismembered. Tumblr did not start collecting and collating data about fandom on the platform until it hired an information scientist in 2013, so much of what happened there—on blogs that have been deleted or renamed—is also impossible to know about unless you happen to have been there and kept notes. Twitter fandom is much more searchable, but it’s also decentralized, and too woven into regular conversation to easily pull out and set aside.

By itself, a website devoted to (possibly fake) dreams about Céline Dion is perhaps not our most urgent archival task. But in aggregate, fansites like Toroptsov’s provide a valuable history of the ways Web 1.0 users exercised fandom to provide their daily lives with context and color. Their joy became the organizing principle of Web 2.0, for a time, but existed side-by-side with it only for a moment.

This is the frame of mind (panic) in which I watched the video for “It’s All Coming Back to Me Now” at Toroptsov’s recommendation. I was at my desk, using earbuds, sitting in silence, feeling an uneasy sense that as soon as it ended, I would feel terrible—like swallowing spoonful after spoonful of marshmallow Fluff and waiting for the piercing stomach cramp to set in. It was too much—too much too much! For days, Dion’s dead boyfriend drove noisy laps around my head. “There were flashes of light!” Dion shouted in the back of my brain, and there were. It was sublime, and I got it: I understood how watching this video might alter the course of your life, particularly in a way that makes you slightly obsessed with dreams—or nightmares.

When I first emailed him, Toroptsov went looking for some of the bigger fan sites that he remembered from the early aughts. “They all closed as well,” he says. “They all closed either before me or around the time I closed my site. From that, it all moved to social media.” He’s completely uninvolved in online Dion fandom now, and he’s not sure he really thought through the decision to let the site erode. “It was kind of a sudden change. Now that you say this, I realize that maybe I shouldn’t have done it,” he says. “It’s such a specific URL. Céline Dreams. I was stupid enough to let it go.”

Looking back, Toroptsov says, Céline Dreams was the prototype for his entire career. For his first major project as a photographer, he borrowed a dress owned by Marilyn Monroe, and traveled the world, photographing her biggest fans interacting with it. He still accepts dream submissions on his website, although they no longer have to be about Dion specifically. He says he’ll feel close to her forever. Sometimes, he daydreams about what it would be like to be her next-door neighbor. “I would say Hey Céline, do you have some salt? Oh by the way, and then we would start chatting.”

from Technology | The Atlantic https://ift.tt/2Tc3B1l