Jesse Aguirre’s workday at Slack starts with a standard engineering meeting—programmers call them “standups”—where he and his coworkers plan the day’s agenda. Around the circle stand graduates from Silicon Valley’s top companies and the nation’s top universities. Aguirre, who is 26, did not finish high school and has so far spent most of his adulthood in prison; Slack is his first full-time employer. But in the few years he has been writing code, he has cultivated what is perhaps the most useful skill in any software engineer’s arsenal: the ability to figure things out on his own.

Aguirre, along with Lino Ornelas and Charles Anderson, make up the inaugural cohort of Next Chapter, an initiative launched by Slack, in partnership with the Last Mile, the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, and Free America, to help formerly incarcerated individuals land jobs in tech. Last year, when Next Chapter launched as an apprenticeship program at Slack—but didn’t guarantee full-time employment—Alexis C. Madrigal wrote in this publication, “Offering an apprenticeship rather than a permanent job may not seem like a huge distinction, but multiple advocates for formerly incarcerated people called attention to this part of the program design.”

It was a fair point. Silicon Valley has often taken symbolic steps toward making the industry more equitable but has under-delivered on lasting change. In June, however, just days before Slack’s IPO, Aguirre, Ornelas, and Anderson were all offered full-time positions, complete with stock options. For Aguirre and his friends, this raised a new question: Could they make it? Access to an elite organization does not necessarily translate, of course, to success. “It’s true that nothing stops a bullet like a job,” Katherine Katcher, the executive director of Root & Rebound, a California-based reentry program, told me. “But reentry is complicated—a job alone without support is usually not enough.”

[Read: Big Tech’s newest experiment in criminal-justice reform]

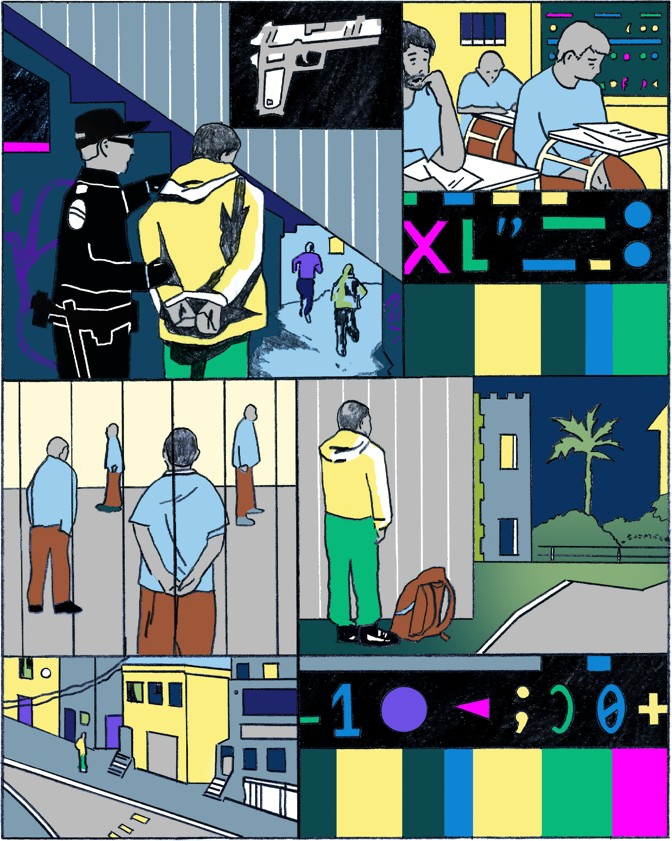

For formerly incarcerated individuals, the stakes of finding, and keeping, a job are high. Almost two-thirds of those released from California’s prison system return within three years. Full-time employment is one of the most effective levers to reduce recidivism, but it isn’t easy to find work when you have spent much of your adult life behind bars. For various reasons, including discrimination against people with a criminal record, the unemployment rate for people who have been incarcerated is more than six times the national average.

“When I got my job offer, I felt like a guy from college getting drafted to the NBA,” Aguirre told me recently over the phone. “But with my background, I also feel like I have a lot to prove.”

Aguirre was first exposed to software development as an inmate at Ironwood State Prison, a rural California prison known for its sweltering summers and progressive rehabilitation programs. For the first month of the Last Mile, a program that teaches business and software skills in prisons, Aguirre and his fellow students didn’t have access to computers. They relied on books and pens to scribble out code on scratch paper. For his first project, Aguirre handwrote code to re-create the In-N-Out Burger website using only a printed-out copy of the chain’s homepage as reference.

Drew McGahey, the engineering manager at Slack for all three apprentices, was initially struck by their ability to solve what he called “blank-canvas problems”—those that don’t have prescribed solutions. “Thinking back to their experience, it makes a lot of sense,” he said. “They all learned how to code in an environment where they didn’t have access to the internet. They’ve got drive.”

But from the start, it was clear to Aguirre that the stigma of incarceration does not end when a person is released from prison. Some of Slack’s customers restrict their vendors from allowing people with a criminal record to access their data. All three apprentices were placed on the test-automation team, which writes tests to ensure the quality of other engineers’ code, precisely because it’s insulated from customer data.

Even before starting at Slack, there was the not-insignificant challenge of relocating to Silicon Valley—which Aguirre, Ornelas, and Anderson all had to do in order to accept their positions. All three had been paroled into other jurisdictions. Not only does transferring one’s parole assignment require a long, bureaucratic process, but simply finding an affordable place to live that accepts people with a criminal record—especially in the Bay Area, with its tight housing market—can be a full-time job in itself. Aguirre said he was pressured to leave the first place he lived by a roommate who grew uncomfortable with the idea of living with someone who had been in prison. After staying with a friend for almost a year, he applied for more than 50 apartments before he was able to find a more permanent home.

“Finding a job is one thing—we all know the stigma associated with incarceration makes it really difficult to find work—but the same exists for housing,” said Kenyatta Leal, who is formerly incarcerated himself and now works for Slack as the “reentry manager” for the Next Chapter program.

[Read: How Slack got ahead in diversity]

Leal serves as a player-coach, mentoring Aguirre, Ornelas, and Anderson through issues such as housing, financial literacy, workplace norms, and the multitude of other reentry challenges that he has overcome himself. In addition to working with Leal, Aguirre, Ornelas, and Anderson also each have a technical mentor, a work-culture mentor, and a career coach, and Slack’s nonprofit partners help the apprentices navigate housing, parole, and travel, and educate Slack’s employees on criminal-justice issues. All of this helped Aguirre feel more welcome at the office, despite having come from a different background than those of many of his colleagues.

Aguirre grew up in Lynwood, California, a predominantly Latino community in South Los Angeles. When he was 11, his family moved east to Orange County, and a couple of years later Aguirre became involved with members of a local gang. He was cited by the local police for some minor offenses, like tagging a telephone pole in chalk, but no serious charges resulted.

Then, on March 13, 2010, Ramon Magana, a young man with local gang affiliations, was shot with a shotgun carrying bird-shot ammunition. Witnesses at the scene said that Aguirre was not the shooter, but, according to police testimony, he had handed the gun to the person who eventually committed the crime. Aguirre was charged as an adult with attempted murder, assault, and gang affiliation. A few weeks after he turned 18, he was shipped off to prison with a life sentence.

Aguirre’s sentence spurred a public outcry. In 2014, a California Court of Appeal determined that Aguirre had “ineffective” counsel and that his sentencing “raised issues of cruel and unusual punishment.” In a resentencing hearing, his time was reduced to seven years, plus a state-mandated 10-year enhancement for gang-related activity. Then, on Christmas Eve, 2017, Aguirre learned that Jerry Brown, then the governor of California, had decided to cancel the 10-year enhancement, citing Aguirre’s exemplary behavior and work ethic in prison. By that time, Aguirre had gotten his GED, completed the coding boot camp, and served nearly eight years behind bars. He was up for immediate release.

The prior year, Slack CEO Stewart Butterfield and a group of coworkers had visited a Last Mile program at San Quentin State Prison, just north of San Francisco. Butterfield was particularly impressed by the program’s rigor and the quality of the software the inmates were producing. Around the time Aguirre was released, Slack started laying the groundwork for what would eventually become Next Chapter.

The goal of Slack for Good, the company’s philanthropic arm, is to increase the number of underrepresented individuals in tech. “Two of our key values as a company are being inclusive and having empathy,” said Deepti Rohatgi, the head of Slack for Good. “This program was not only a way to move the needle on an incredibly important issue in the United States, but also to make it very clear to our employees that these values matter to us.”

Of the ten people who underwent the rigorous interview process for Next Chapter—a process similar to how Slack interviews any entry-level software engineer—Aguirre was one of the three chosen.

“If you want to understand a societal issue, you have to get close to it,” said Leal, who, as an inmate at San Quentin, also went through the Last Mile program. While on the inside, Leal met Duncan Logan, the CEO of a tech accelerator called Rocketspace. After Leal was released, he went on to work for Logan for five years. “It’s a huge paradigm shift—going from living in a 6-by-9-foot cell and having very little decision-making power in your life to all of a sudden being part of the 21st-century gold rush,” Leal said.

Now, Leal not only helps the apprentices acculturate but also, perhaps more importantly, helps the rest of the company learn about what it means to be formerly incarcerated in the United States. With more than 600,000 people returning to society each year, a company hiring three formerly incarcerated software engineers doesn’t do much to address the scale of the reentry challenge. “Programs like the one at Slack help returning citizens feel their worth and dignity,” said Katcher. “But I want to caution the movement to get tech to propose solutions to all of society’s issues. We need to applaud companies like Slack, but know that the nitty-gritty of human services—housing, health care, social support—which lots of nonprofits and public institutions are working on, the private sector has largely turned away from.”

A spokeswoman for Slack said the company recognizes that this one project won’t solve broader reentry challenges, but she noted that the company hopes, internally and through its nonprofit partnerships, to help address issues faced by its formerly incarcerated hires.

Aside from affecting the lives of Aguirre, Ornelas, and Anderson, the largest change as a result of Next Chapter may be a shift in perspective—among Slack’s employees and, with luck, the tech industry as a whole. Slack has already been outperforming some of its Silicon Valley peers when it comes to hiring diverse talent. Creating a blueprint to hire formerly incarcerated engineers—and, more broadly, changing how employees think about those who have been imprisoned—may catalyze a larger shift in public opinion. Slack has held multiple company-wide meetings on criminal justice, including “reentry simulators” in which employees act out the challenges people face when leaving prison, such as applying for housing or registering with the Department of Motor Vehicles. In the past few years, more than 200 employees have visited San Quentin to mentor and learn from aspiring tech workers on the inside.

“When we first came into Slack, there was fear,” Leal acknowledged. Some employees were hesitant to work alongside formerly incarcerated coworkers; others thought the program might distract from more important priorities. But through talking to Slack employees, he said, he was able to help change their attitudes.

Six months into his full-time job at Slack, Aguirre’s life is peaceful. At work, he’s become one of the more senior members of his team, so new hires come to him for advice. He runs a coding group on Fridays to help other engineers at the company understand how the test-automation process works. Most days, he has lunch with Ornelas and Anderson. “I appreciate the small stuff now—being able to get dropped off anywhere, ordering Uber Eats on my phone, hearing my mom on the phone whenever I want,” he said.

Today, Aguirre’s focus is on becoming a better software developer. He wants to transition into a front-end role that would allow him to work more directly with the Slack features that users see. (Building certain features of the app doesn’t require engineers to access customer data.) Recently, in a glass conference room on the top floor of Slack’s San Francisco headquarters, I asked him about his professional ambitions. “I don’t like to think too far ahead because stuff always changes,” he said. “But five years from now, I hope that I have a good track record as an engineer, and that my story has helped a lot of people change their perception of people with my background.” Some of Aguirre’s friends back in Orange County don’t know quite what a software engineer does, but they do know tech. Aguirre tries to encourage them to get into coding, offering to send them books to get started. “I tell them this isn’t like working at an old traditional company,” he said. “This is the new stuff.”

from Technology | The Atlantic https://ift.tt/2LQcqJC